Control of protein synthesis and memory by GluN3A-NMDA receptors through inhibition of GIT1/mTORC1 assembly.

Our brains are constantly bombarded with information about the world around us, only some of which is processed and stored for long periods, in the form of memories. Scientists at the Institute of Neurosciences in Alicante, Spain now shed light on how the brain decides when and what information to keep, and identify a new molecular complex that if correctly targeted might bring back the learning potential that is lost with aging or disease.

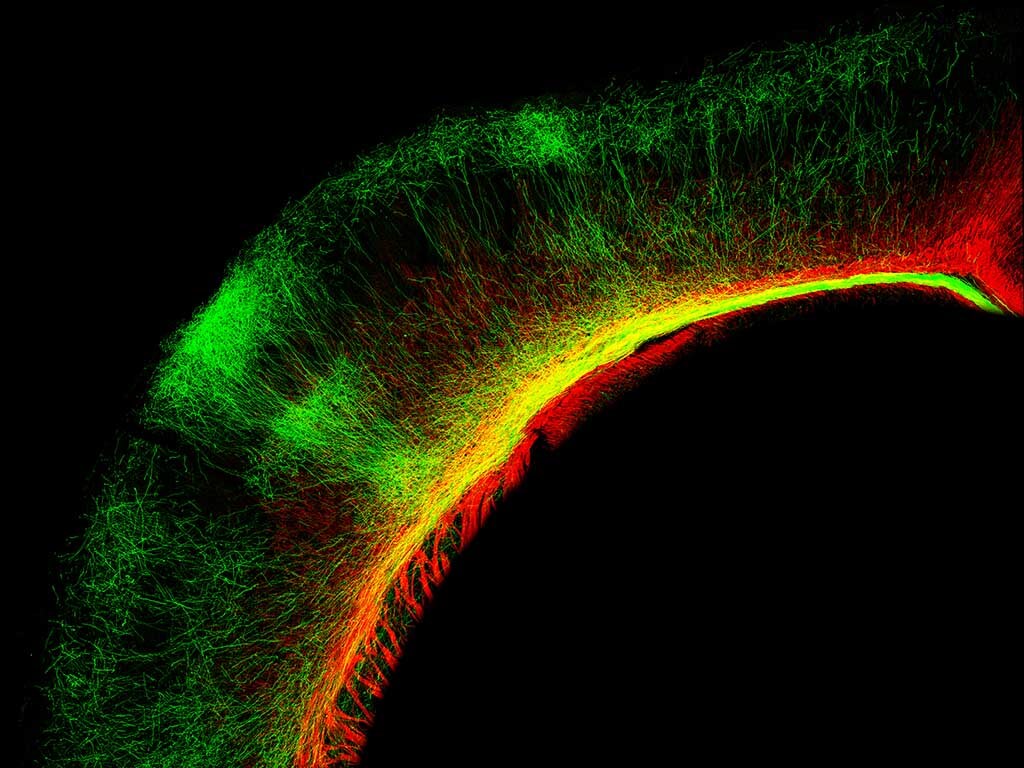

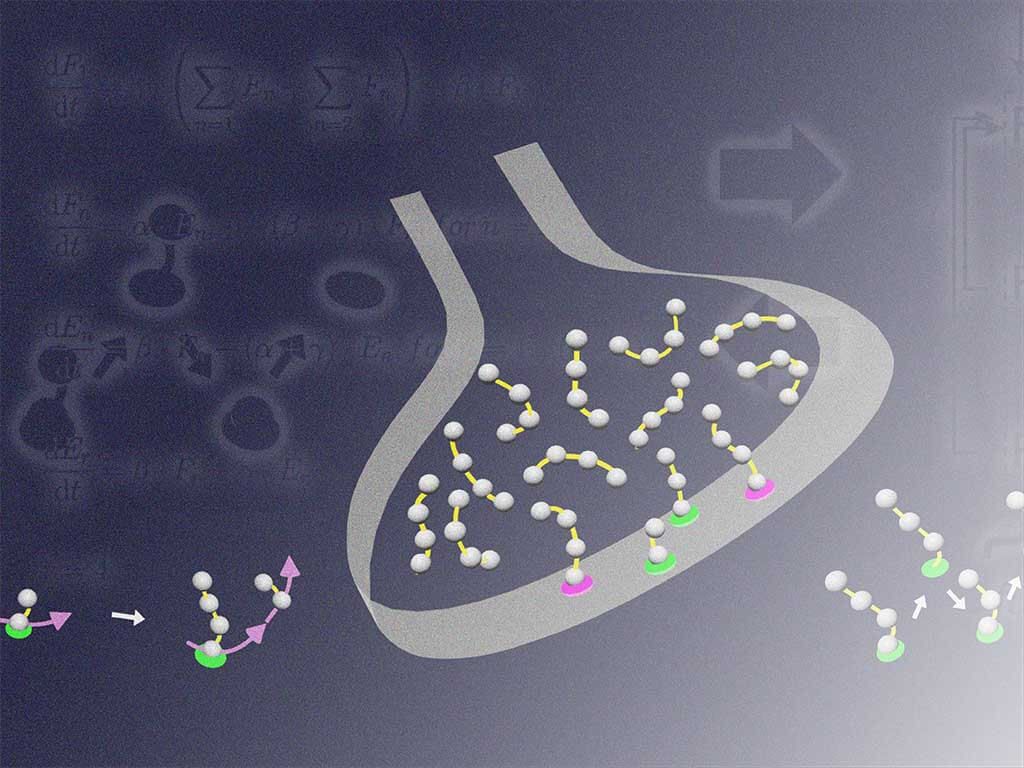

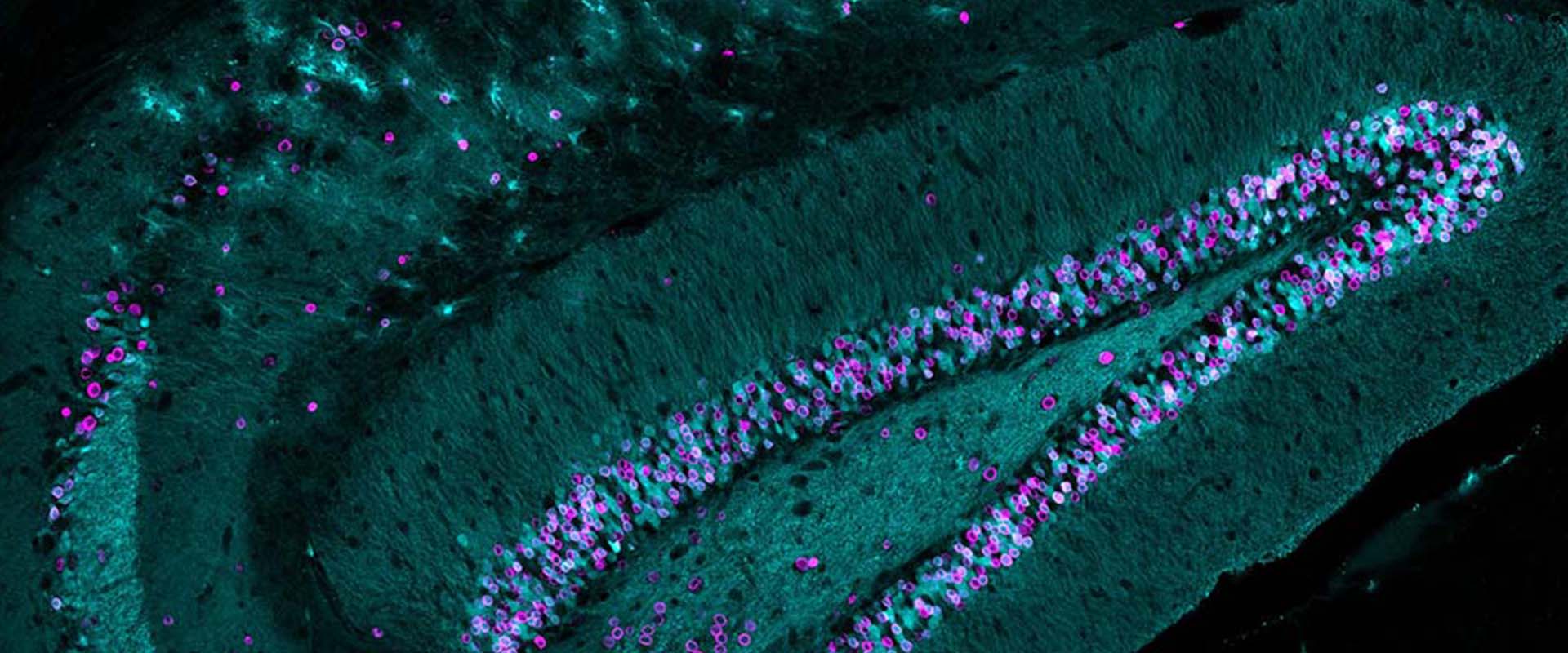

Memories are encoded in the brain as new or stronger synaptic connections between neurons. Some are retained for only a short time, while others are kept for a lifetime. Work in the Pérez-Otaño lab has now identified one of the keys for encoding enduring memories: a signaling complex made of two molecules, mTOR and GIT1, that increases the synthesis of specific proteins. The complex is localized and activated at selected synapses, allowing for precision in memory formation. The researchers found that the signaling complex appears in late postnatal life, which might explain why infant memories are transient, a phenomenon known as infantile amnesia. The complexes are activated by a special family of neurotransmitter receptors – NMDA receptors – that have long been known to be important for memory formation. Intriguingly, the researchers also discovered that instead of activating the complex, one of the family members actively limits activation, and removal of this “brake” allowed mice to learn difficult tasks better and more durably.

The group is pursuing these findings as a potential approach to combat cognitive decline that occurs naturally with aging or is associated with developmental or neurodegenerative brain diseases.

English

English