Regulation of Cerebral Cortex Folding by Controlling Neuronal Migration via FLRT Adhesion Molecules

Along evolution, the brain has been growing. In order to increase its size, the cerebral cortex, the most evolved part of the brain containing its higher functions, had to fold. Accordingly, we have a cerebral cortex the surface area of which is three times larger than if it was smooth, which implies more space to execute higher functions such as reasoning, planning, perception or action. However, cerebral cortex folding does not occur in all mammalian species. It is limited to those having a big brain, such as whales, dolphins, dogs, ferrets and humans, while rats and mice have a smooth brain. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Neurobiology in Munich and the Institute of Neuroscience in Alicante have found proteins critical for brain folding.

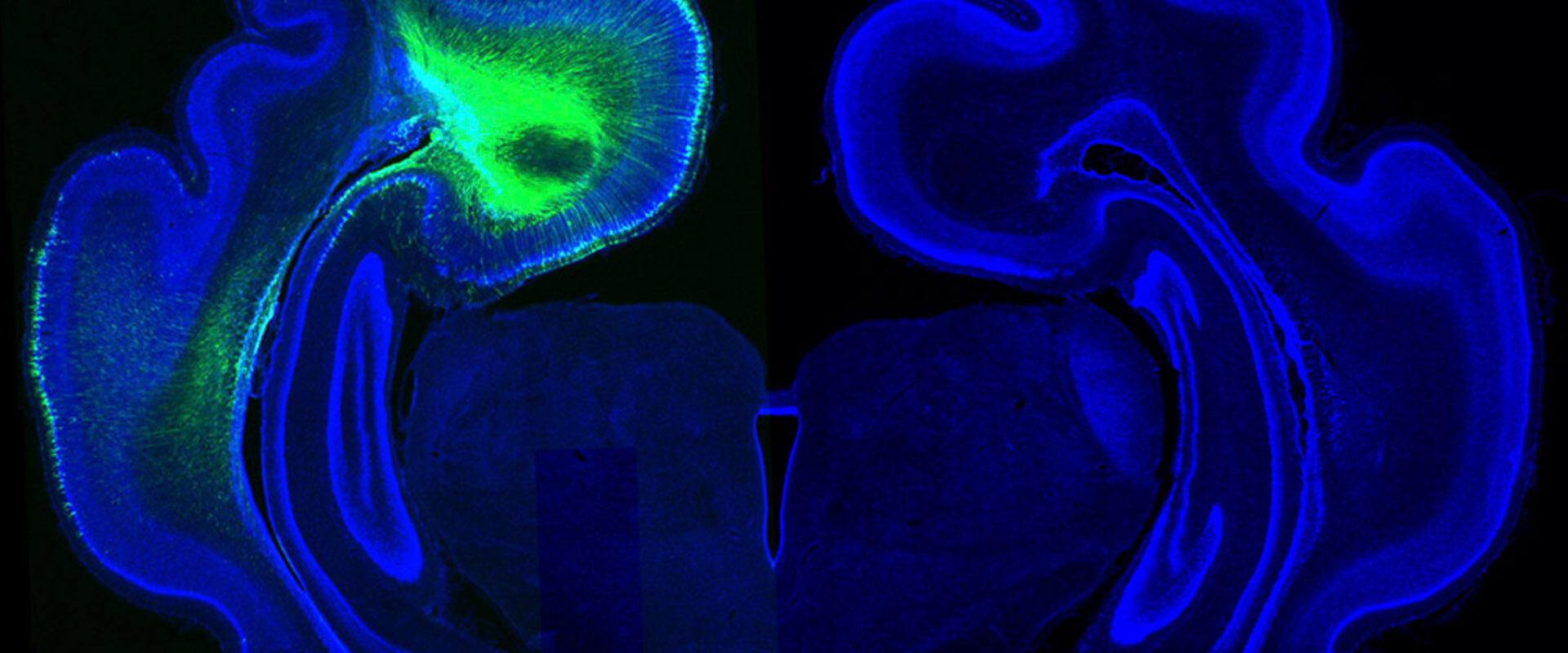

During brain development, neurons travel from their site of birth (in the inner zone) to the most external part, the cortex, traveling long distances. In animals with a smooth brain, like mice, cell adhesion proteins FLRT regulate these neuronal migrations, providing adhesion between nerve cells, which align giving rise to a smooth surface. In the brain of humans and other mammals, like ferrets, there is much less amount of these proteins. To find out if they have an important role in the folding process, we created a mutant mouse lacking two FLRTs (1 and 3), and found that in their absence the resulting cerebral cortex develops with fissures resembling those in the human brain. Until now this has only been achieved by acute manipulations, but never in a mutant mouse line. This is very important because it provides us, finally, of a very robust tool. This international collaborative work together with Max Planck Munich has allowed us to discover a new mechanism of fissure formation in the cerebral cortex that is completely different from that known so far for fold formation, discovered by our lab and related to cell proliferation. This novelty forces us to consider that brain folds and fissures form via the combined regulation of proliferation and migration.

In addition to checking in ferrets, transcriptomic data in human embryos from this study support that our results may be extensive to our species. Hence, these results are an entry point for other studies of normal and pathologic brain folding. In human beings, cortical folding begins at around gestational week 20 and is complete at about 1.5 years of age. However, occasionally folding foes not occur correctly and leads to a group of rare diseases, including lissencephalies, which are malformations of cerebral cortex development due to alterations in neuronal migration. These malformations are accompanied by epilepsy, motor alterations and cognitive delay. Although our discovery could eventually help to correct these diseases, for now it helps to understand them and thus to find new potential genetic causes, to ultimately do genetic diagnosis. We ignore the genetic cause of neurodevelopmental malformations in 60-70% of children, and this lack of knowledge is a terrible void for the parents.

Español

Español