SNAP-47 mediates somatic oxytocin dynamics in hypothalamic neurons.

Scientists discover a key mechanism regulating how oxytocin is released in the mouse brain

• A study led by the Institute for Neurosciences CSIC-UMH has identified an essential protein responsible for the slow and sustained release of oxytocin in the brain, a process that is fundamental for the regulation of social behavior.

• This work, published in Communications Biology, provides new insights into how the brain maintains basal levels of this hormone and how subtle adjustments in its release modulate sociability.

(Photo: IN CSIC-UMH researchers Beatriz Aznar Escolano and Sandra Jurado. Source: IN CSIC-UMH)

The brain does not only communicate through fast electrical impulses; it also relies on slower, more diffuse chemical signals that modulate our emotional and social states over time. A study led by the Institute for Neurosciences (IN), a joint center of the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) and the Miguel Hernández University of Elche (UMH), has identified a key molecular mechanism that regulates the release of oxytocin within the brain. Published in the journal Communications Biology, the work sheds light on how this hormone maintains a “social tone” and how its release contributes to the quality of social interactions.

Link video: https://youtu.be/9daJYmiUj5Y

Oxytocin is a hormone widely recognized for its role in emotional bonding, sociability, and emotional regulation. Unlike classical neurotransmitters such as glutamate or GABA, which are released quickly and locally from neuronal axons, oxytocin belongs to the group of neuropeptides and can also be released from the cell body (soma) and dendrites. This slower, more diffuse type of release affects broad regions of the brain, yet its underlying molecular mechanisms have remained largely unknown—until now.

“We knew that oxytocin is released within the brain from compartments other than the axon, but we had limited understanding of how this process is regulated”, explains researcher Sandra Jurado, who leads the Synaptic Neuromodulation Laboratory at the IN CSIC-UMH and headed the study. “Our work focuses precisely on understanding the mechanisms that enable this slow and sustained release, which likely prepares the brain for social interaction”, she adds.

A Key Protein for Unconventional Release

In this study, the team identified the protein SNAP-47 as an essential component of the machinery that enables the transport and release of oxytocin from the soma and dendrites of hypothalamic neurons—the brain region where this hormone is produced. SNAP-47 belongs to the SNARE family of proteins, which are involved in vesicle fusion and the release of chemical signals, but it displays distinctive properties: “While other proteins in this family mediate fast and highly efficient release, SNAP-47 operates more slowly”, explains Beatriz Aznar, first author of the study. “This fits well with the type of release we observe for oxytocin within the brain, which does not occur in rapid pulses but rather in a more sustained manner”, she adds.

This difference is key to understanding oxytocin’s function in the central nervous system. Oxytocinergic neurons in the hypothalamus send their axons outside the brain to release the hormone into the bloodstream. However, within the brain, the oxytocin that modulates social behavior is largely released from the soma and dendrites of these neurons through a mechanism that is independent of axonal release.

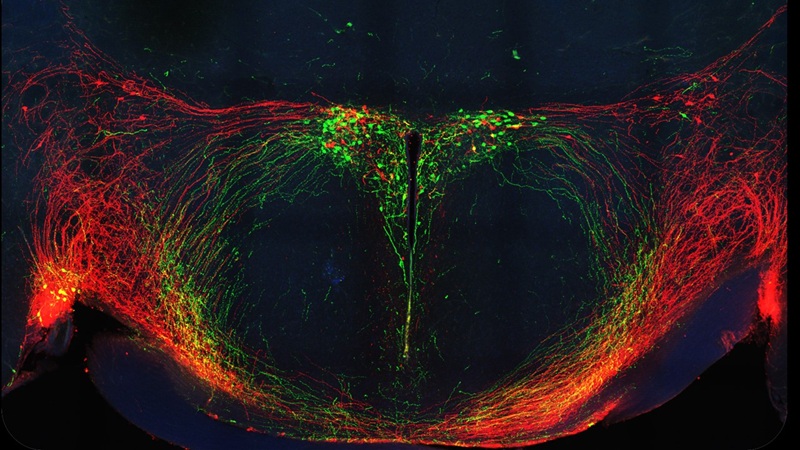

Confocal microscopy image showing oxytocin (green) and vasopressin (red) circuits in the mouse hypothalamus, both of which are highly relevant for regulating social behaviors in mammals. Author: Mª Pilar Madrigal

Experiments in Cell Culture and Animal Models

To unravel this process, the team combined experiments in neuronal cultures with studies in mice. In an initial phase, they examined how reducing SNAP-47 affected vesicular trafficking and oxytocin release in cultured cells. They then extended these findings to animal models using genetic manipulations specifically targeted to oxytocin-producing neurons.

The results showed that reducing SNAP-47 expression disrupts oxytocin release from the soma and dendrites, without affecting the classical mechanism of axonal release. This alteration had functional consequences for the animals’ social behavior: although the mice still displayed sociability, their interactions were shorter and less robust.

“The effects are subtle, but highly revealing”, explains Jurado. “This is not a complete loss of sociability, but rather a fine-tuning of the quality of interactions. This suggests that this release pathway maintains a basal level of oxytocin that primes the brain to respond appropriately to social stimuli”.

The authors suggest that this mechanism may function as a background system that regulates the brain’s social state, maintaining a steady flow of oxytocin that modulates processes such as social anxiety, motivation, and the propensity to interact. “It represents a basal tone that does not trigger strong responses on its own, but that shapes how we react when a relevant social stimulus appears”, Aznar explains.

This finding broadens our understanding of how hormonal signaling is regulated in the brain and opens new avenues of research into how subtle alterations in these mechanisms could contribute to neuropsychiatric disorders in which oxytocin plays a significant role. “The next step will be to identify the remaining components of this molecular machinery and understand how the different modes of oxytocin release are coordinated to produce a coherent response”, Jurado concludes.

This study was made possible thanks to funding from the Spanish State Research Agency–Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities, the Prometeo Programme of the Valencian Regional Government (Generalitat Valenciana), and the Severo Ochoa Programme for Centres of Excellence.

Source: Institute for Neurosciences CSIC-UMH (in.comunicacion@umh.es)

Español

Español